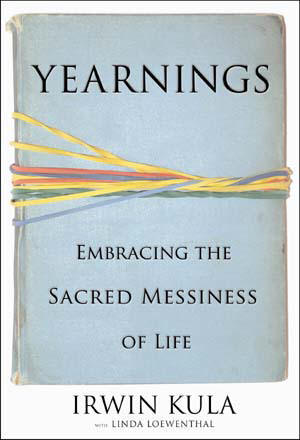

NEW BOOK!!!

YEARNINGS: Embracing the Sacred Messiness of Life

by Irwin Kula

September 2006

$23.95US (hardcover);

336 pages; ISBN:1-4013-0192-4

To order Yearnings from Barnes & Noble, click here.

To order Yearnings from Amazon, click here.

An Excerpt from Chapter 2, Yearning for Love...

FORGIVENESS

“LOVE MEANS NEVER HAVING TO SAY YOU’RE SORRY,”

ARE the words spoken by Ali McGraw in that classic ‘70s movie, Love Story.

This line captures a yearning so many of us have, even if we don’t want to

admit it. We long for someone who understands us and accepts us so fully –

despite all our faults and mistakes – that apologizing seems beside the

point. The ultimate relationship, we can’t help but think, is one in which

forgiveness is easy, free-flowing and immediate; where it requires little or

no effort from either party, even when the hurt may be deep.

Of course, it’s just the opposite. Our most

loving relationships are those in which we say “sorry” continuously.

Forgiveness is central to the workings of love. If we’re not seeking and

receiving, being asked for and granting forgiveness on a regular basis, it’s

most likely that our relationship is not as intimate, dynamic, or alive as we

think it is. And it’s likely that we’re holding in plenty of bitterness,

resentment, guilt and shame. Quite simply, things aren’t messy enough. One

could say that forgiveness is the glue of loving relationships, holding it all

together and in need of constant renewal and repair. But there is no such

thing as “an act” of forgiveness. Forgiveness is a process, a way of being in

the world.

I hear so often about the hurts that won’t go

away: the person who holds a grudge, who nurtures a resentment; or the one who

never admitted his wrong, who simply can’t humble himself to ask for

forgiveness, although it’s clear he’s burdened by the not asking. The

yearning to forgive and be forgiven is palpable. We want to make our

relationships right, to make things whole again. A recent Gallup poll

reported that 94 percent of Americans say forgiveness is one of the central

virtues. Yet 48 percent of those same people say they’ve never had a forgiving

experience. How can this be?

Perhaps it’s because the forgiveness so many of

us year for is total and complete. When people talk to me about forgiveness,

they want so badly to be able to start again, to have everything be okay, to

wipe the slate clean. Before they open themselves up again by either granting

or seeking forgiveness, they want some guarantee that it will all work out.

They imagine a single conversation that will end in tears or laughter, at the

end of which both parties will be able to go on as if nothing had ever

happened; the hurt and disappointment having been erased or healed. When this

doesn’t happen, one person may become defensive, giving up too soon. Some

grant forgiveness too quickly, wanting to let the other person off the hook,

wanting to feel better themselves, to retreat from the pain and uncertainty.

Others tell me they want to simply let it go, to forgive someone on their own

without interacting with or confronting the person at all. Or they think it’s

possible to forgive themselves. Anything but approach or confront another

person.

This is understandable: few Things make us as vulnerable as admitting our mistakes, especially to someone we have every reason to think will be angry at us or, even worse, unreceptive or shut down. When we ask for forgiveness, there’s no place for defenses, for justifications. We have to make ourselves naked. At the same time, to forgive is an act of faith and trust. There’s little reason to expect that the transgression won’t happen again; once someone crosses a line, what’s the guarantee they won’t again? We live in a culture of avoidance; few of us have had models of forgiveness or were taught that feeling vulnerable and taking risks is a necessary part of intimacy. So, instead, we seek a kind of cheap grace.